About Applied Behavior Analysis

WHAT IS ABA?

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is a science-based field devoted to understanding the relationship between behavior and the environment. Behavior is explained and examined by methods of scientific inquiry such as objective description, quantification, and controlled experimentation (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). It differs from other disciplines of psychology that appeal to mentalistic concepts such as the mind, psyche, unconsciousness, or other models that are beyond the physical world and cannot be empirically validated (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007 & Johnston & Pennypacker, 1993).

ABA has many facets and defining characteristics that separate it from other therapies. As referenced in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, the seven dimensions of ABA enable the field to become best known as the gold standard for its success when it comes to providing therapeutic services to people with a developmental disability (e.g., autism, down syndrome, intellectual challenges) (Baer, Montrose, & Risley, 1968).

Below are the seven defining characteristics of ABA, as written in “Some Current Dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis” (Baer, Montrose, & Risley, 1968).

- Applied. This simply means that we put practical use to theories. This is the “do” part of ABA. Applied, only observes elements of behavior that are likely to change and socially significant to the person seeking treatment (Baer, Montrose, & Risley, 1968). When behaviors that are socially significant to people are selected to be modified, the intervention can drastically improve people’s lives.

- Behavioral. A behavior is a manner in which one acts in response to a particular situation or stimulus. To define therapy as ABA, the behavior in question must have certain qualities about them. The behavior must be measurable, in need of improvement, and able to be monitored when change occurs.

- Analytic. As data is collected and measured on a particular behavior selected for change, the data must show a clear relationship between intervention and a positive change.

- Technological. In this case, the word technological gives way to the meaning that techniques used are comprehensively detailed, identified, and described. All of the procedures must be completely defined and documented to allow others the ability to replicate the interventions. This ensures the analytical criteria of the applied therapy. Without a technological characteristic of ABA therapy, there may be a faltering in the other characteristics.

- Conceptual Systems. Systems link concepts and procedures to bring information together. Conceptual systems are a necessary characteristic of ABA therapy because procedures are then described in terms of basic principles of behavior analysis. Basically, the procedures and instructions that are written for treating a client must be written exactly and precisely so that they can be replicated in a different situation with a different client. All of the potential variables must be acknowledged.

- Effective. If you have all of the above characteristics, but the usage of behavior techniques are not adequately changing the behavior, this indicates that the therapy is not effective, and would not be characterized as a defining characteristic of ABA. Outcomes must be meaningful for the participant and are cost-effective and efficient.

- Generalized Outcomes. The behavior change that occurs in ABA can cause a domino effect of other behavior changes that are not directly treated by the intervention. The behavior change will also last over time, and appear in new environments.

What sets ABA Apart?

The goal of understanding and improving the lives of people with or without a developmental disability is common in other fields when it comes to helping people. One of the key aspects that sets Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) apart from other professions that have a similar intent in helping people lies in its focus and methods. Since behavior is explained and examined by methods of scientific inquiry such as objective description, quantification, and controlled experimentation (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007); it differs from other disciplines of psychology that appeals to mentalistic concepts such as the mind, psyche, unconsciousness, or other models that are beyond the physical world and cannot be empirically validated (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007 & Johnston & Pennypacker, 1993).

Since the focus of ABA is on current behaviors and their changes with the client’s environment, it changes the way that applied behavior analysts view a particular behavior in a certain situation (event). In other words, part of the reason for ABA’s success in improving the lives of people with or without a developmental disability is because behavior is explained through observable events (e.g., actions) that can be measured and quantified.

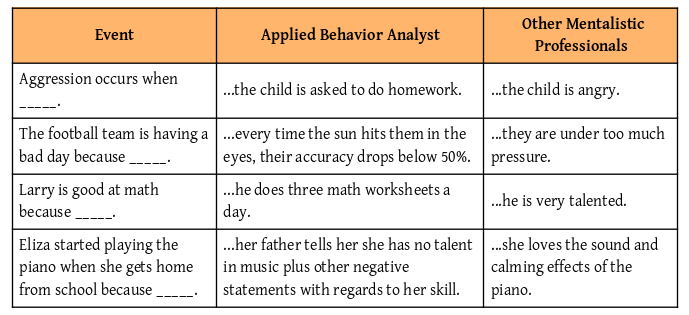

For example, if a parent wanted to decrease their child’s aggressive episodes. A necessary question to ask is when does this behavior occur? In other mentalistic fields, aggression may be viewed as occurring when the child is angry. Since there is no way to directly quantify how angry someone is, ABA would take a different approach. An applied behavior analyst may observe that aggression occurs every time that the child is asked to do homework. This can be directly quantified by finding the probability of aggression occurring every time the child is asked to do homework. Once that is identified, a solution can be directly tailored to that child.

Table 1 shows the difference between how an applied behavior analyst would view a specific event, versus how a psychologist (or another mentalistic professional) may view the same event.

Table 1: Examples on how different fields view the same situation.